This blog post was written by Malte Vollmerhausen and Marc Stauffer.

Imagine you are going to a supermarket. You spot a pyramid of Campbell’s tomato soup cans. They are off by 10%. You take a bunch of cans and buy them. As a study shows, you statistically would have bought around 3 cans. Let’s sit into our Dolorian, go back 30 minutes and enter the supermarket again. You’re again seeing the pile of Campell’s (with the 10% discount), but now there is one little addition: a sign saying “Max. 12 cans per person”. As the study states, this time you would bring 7 cans to the cash-point. You made a completely irrational decision, because the sign should in no way have an effect on your decision making process – yet it does. As you can imagine, this problem is also present when facing security decisions.

Imagine you are going to a supermarket. You spot a pyramid of Campbell’s tomato soup cans. They are off by 10%. You take a bunch of cans and buy them. As a study shows, you statistically would have bought around 3 cans. Let’s sit into our Dolorian, go back 30 minutes and enter the supermarket again. You’re again seeing the pile of Campell’s (with the 10% discount), but now there is one little addition: a sign saying “Max. 12 cans per person”. As the study states, this time you would bring 7 cans to the cash-point. You made a completely irrational decision, because the sign should in no way have an effect on your decision making process – yet it does. As you can imagine, this problem is also present when facing security decisions.

“Understanding how our brains work, and how they fail, is critical to understanding the feeling of security” [1]. Psychology and security, or maybe rather the security decisions we make day in and day out, are closely related to each other. There has been a lot of research in the area of human behaviour and decisions making, and as it turns out, particularly when looking into the field of security, we make a ton of bad security trade-offs.

In this blog post we want to give you a better understanding on how our mind tricks us and why these situations are so critical to improve one’s overall security level. We will start with some basic knowledge about psychology and will take a deeper look into an array of cognitive biases. After understanding the basic principles and biases, we want to connect the dots of what we just learned to the security topic and see, where and why a lot of mistakes happen. Finally, we will give some practical advice on how to avoid making bad security decisions.

Fundamentals

Following the general understanding of the word “psychology”, it describes “the science of the mind and behavior” or “the way a person or a group thinks” [2], whereas the correlation between our mind and our behavior plays an important role. Before acting in a certain way, we foremost need to make a decision about what we will do and how we will do it. This decision making process is critical. As Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman describes in his New York Bestseller “Thinking fast and slow” [3], our brain uses two systems regarding the decision making process. He characterizes the two systems as follows [3]:

- System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.

- System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice and concentration.

A typical example for System 1 is a situation in which you spot an angry face. You immediately recognize the facial expression and interpret it in a certain way. You even anticipate that this person might shout or act violently in the next moment. This all happens in an instant.

System 2 comes into play when you see an equation like “24×17”. If you don’t have an autistic touch, you won’t be able to solve this equation immediatelly. You might know that the solution must be higher than 100, but actually solving the equation takes a bit of time and effort.

Talking about System 1, there is a method you’ve probably already heard of called “heuristics”. A heuristic is generally defined as “[a] simple procedure that helps finding adequate, though often imperfect, answers to difficult questions” [3]. Heuristics are evolutionary-based. As we already mentioned, the problem of System 2 is that it requires effort and focus, and that it’s only possible to do one challenging task at a time. Our ancestors needed to make quick fight-or-flight decisions in order to survive. The one’s being focused on observing a beautiful sunset while a lion sneaked upon them did not survive. It was mandatory to make quick decisions and this we continue to use this kind of behaviour, even though our lives have become safer so that we would have the chance and time to use System 2 – but sadly we often do not. The same problem arises when answering questions, because we most of the time we do not answer the actual question, but a heuristic one. Here are some examples [3]:

| Target Question | Heuristic Question |

| How much would you contribute to save an endangered species? | How much emotions do I feel when I think of dying dolphins? |

| How happy are you with your life these days? | What is my mood right now? |

| How popular will the president be in six months from now? | How popular is the president right now? |

Let’s take a quick look at the first example. You don’t give an answer by System 2, but rather something that comes from System 1. You don’t think about what the extinction of dolphins would mean to our economy, if it would bring the food chain out of balance or ask other rational questions. You are asking System 1 for a quick (imperfect) answer and you find this answer by asking an easier question: “How much do I like dolphins?”

As we can see, the main challenge is our disproportionate use of System 1 and the irrational decision we thus make. The subsequent deviations in judgment leading to irrational decisions are generally known as “Cognitive Biases”.

Cognitive Biases

Let’s go back to the supermarket from the beginning for a second. One person buying 7 cans instead of 3 just because of a sign limiting the maximum buyable amount of cans per person is nothing special. But the important aspect about cognitive biases is their systematic nature. Thousands of persons changing their shopping behaviour in a predictable manner in reaction to a simple trick of course catches the attention of marketing specialists and store owners. And it’s not just about purchasing decisions. Cognitive Biases influence what we vote for in elections or the next salary negotiation with our boss – all without us even noticing. Their broad distribution and stunning effects is what has inspired over six decades of ongoing research on judgment and decision-making in cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioral economics, leading to an ever growing list of known heuristics and biases our mind is prone to fall for [4]. Looking at them and related research we see some common issues concerning how our brain deals with reality. In the following we will discuss some of the most striking heuristics and biases that affect our decisions in general as well as our behaviour regarding security. While some of these effects might sound hard to believe, all of them have been proven in multiple studies by renowned researchers and psychologists.

Most of the time when making decisions we only have a limited amount of information available to us to evaluate our options. The problem is that we don’t know what we don’t know – we don’t think about the information that is missing. When we encounter a problem during a project we actively turn to google to get an overview of possible solutions. But something completely different happens for all the small decisions we make day in and day out. When meeting someone new at a party it takes us less than a minute before knowing whether we like them or not. Our brain takes the information available and uses it to interpolate a coherent picture of the person in front of us although we first met them just a moment ago. What doesn’t happen is that we take a step back and question our initial impression. Studies show that interviewers screening job applicants often come to a conclusion in less than 30 seconds after the beginning of the interview – deciding for a less-than-optimal candidate more often than not. The fact that we are mostly oblivious to information not directly available to us was first discovered by Daniel Kahneman. He sums it up as: What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI). A special incarnation of WYSIATI explains our irrational behaviour when buying cans of soup and is called Anchoring.

Anchoring

Everytime we deal with numbers, the first value that gets thrown at us influences any further thoughts. Once such an ‘anchor’ has been set our mind is inevitably dragged into a range of values closer to the one first mentioned. This has been confirmed in a famous experiment by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. The two israeli researchers put students in front of a wheel of fortune and had them write down the number generated by the wheel. While the participants believed the number to be truly random, the wheel was in fact manipulated to either stop on the values 10 or 65. When after that the participants were asked to guess the proportion of african states in the UN, the average guesses were 25% (persons anchored to 10) and 45% (persons anchored to 65). The participants estimations of the proportion of african states in the UN were significantly altered by random, unrelated numbers generated by a wheel of fortune! Challenged by these surprising findings, many researchers went on to put the effect of anchoring to the test – with even more bewildering results: the same effect was found with people instructed to guess the maximum height of mammut trees (86m when anchored with 55m, 257m with an anchor of 366m), to donate for seabirds in danger of extinction (20$ following an anchor of 5$ versus 143$ when anchored to 400$) or estimate the value of real estate for sale (being influenced by the anchor by 43% after being confronted with prices twelve percent over or below market value of the house in question). The dangerous consequences of the anchoring effect are best illustrated by an experiment conducted with judges told to decide the sentence of a shoplifter. After getting anchored to either 3 or 9 by rolling a loaded dice, the participants would have sent the defendant into prison for the time of either five months or eight months. It does not take a lot of imagination to see how an effect like that can be a problem for security. And getting severely affected in our thinking by some external setting is not just limited to numbers as we will see in the following section.

Priming

External conditions – that we are not even consciously aware of – can severely affect our behavior in a number of ways. All the time during our day to day life, our brain subconsciously adapts to the current situation by analyzing our surroundings and anticipating future events and actions. This happens while you read the newspapers in the morning, when you walk through the supermarket or as soon as you enter a new restaurant. To make sense of all the stuff happening around you, your brain tries to find patterns and groups multiple findings to superordinate categories – a process that researchers call “priming” and that is often used in studies to put participants in a certain mindset to analyze the resulting changes in their behavior. A popular method used by researchers to prime candidates to a certain topic is instructing them to build sentences out of related words, without mentioning the topic directly. One such study that soon gained popularity as “The Florida Effect” found participants walking significantly slower after being primed to the topic “age”, another one saw participants completing the fragment so_p a lot more often to the word soup rather than soap after they had heard the word eat beforehand. Things get a lot more interesting though as we turn to priming in the context of voting. A study analyzing voting behavior in electoral districts in Arizona in 2000 found people to be a lot more likely to support proposals to increase government spending on education when they cast their vote directly inside a school rather than just in proximity of a school, while a different experiment saw a significant increase in support for school initiatives when the respondents were shown pictures of classrooms and school lockers first. At this point it is fairly easy to see that simple external conditions influencing decisions as important as what to cast your vote for can quickly get problematic – even more so as soon as someone tries to use this effect to intentionally manipulate people’s decision-making. As always, we can stir up the situation even more by putting money into play – as Kathleen D. Vohs has done in a number of studies. She documented that people that had first been primed to money (by a stack of monopoly money in the background or a screensaver showing floating currency) were acting more independently, preferred to be alone, were more selfish and less likely to help others. Despite all of these findings, there is also a positive side to priming that can be used by everyone of us to make the world a happier place. Simply put a broad grin on your face (or stick a pencil between your teeth) and your mood will indeed brighten, as evidence suggests – proving right common sayings like “grin and bear it” or “a smile a day keeps the doctor away”.

Statistics and Numbers

In the section about the Anchoring-Effect we already saw one of the issues we face when dealing with numbers. Further investigation into our minds numerous heuristics and biases show that anchoring is not an isolated effect, but rather that we get numbers and statistics wrong nearly all the time we are subconsciously confronted with them. One of the first issues in that regard is the fact that we perceive the same number differently simply depending on the way it is presented to us. This is well demonstrated by the following example an it’s also already hinting at possible implications for the security topic.

Imagine you are feeling ill and turn to your medicine cabinet to get some pills to fix you up. After reaching for one of the medicaments, you probably first take a glance at the package insert to check for possible side-effects. This information will then guide your decision to take that pill or better reach for another drug with less danger of complications – and making the wrong decision here might turn out painful. Interestingly, your decision will not only be guided by rationally comparing the probabilities but rather by the way they are presented on paper. Researchers discovered that people believe something to be a lot more likely to happen if the chance is described as a fraction (1 out of 100) rather than as a percentage (1%), an effect known as the Denominator Neglect. This even led to participants deeming an illness resulting in 1.286 out of 10.000 people dying to be more dangerous than a condition with a mortality rate of 24%, while the latter is in fact twice as deadly!

Another problem we face when dealing with statistics is the sample size. To decide what measures should be taken to improve a certain situation it is common to look at statistical data. Let’s assume an organisation wants to improve the effectiveness of schools and has to decide on measures to fund with their budget. During their decision-making process the people in charge come across a study stating that the most successful schools on average are small. As a result, significant amounts of money are invested to split up schools and to focus on creating new small schools. This is exactly what happened in a cooperative project involving the Gates Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trust and even the US Ministry of Education. The thing is that a close look at the same statistical data reveals another insight: not just the most successful, but also the schools with the worst results are small on average. The truth is: smaller schools are neither better nor worse than large schools, and a lot of money was mostly wasted. The findings of the study can simply be explained by smaller schools having less pupils and thus a smaller sample size, leading to more extreme results. Our inability to intuitively realize the consequences of a small sample size is known as the law of small numbers.

Many of the errors we make when dealing with numbers and statistics can be explained by the way our brain handles large quantities and probabilities. While our mind can imagine numbers in the range of zero to ten and fractions from zero to 1/10th or maybe 1/100th fairly well, we lack an intuitive model for very large or very small numbers. Unlike a computer, we are not good at solving mathematical equations and calculating or comparing exact probabilities, but are rather good at quickly estimating all-day situations based on our experience. While this works great most of the time, it can lead to totally illogical assessments like the following.

People were given the following two statements and asked which one they thought was more likely to actually happen:

- A massive flood somewhere in North America next year, in which more than 1.000 people drown.

- An earthquake in California sometime next year, causing a flood in which more than 1.000 people drown.

If you take some time to analyze these statements it becomes obvious that statement 1 must definitely be more likely to happen. Some event (like a massive flood killing over a thousand people) is always more likely than the same event with an additional condition (e.g. an earthquake causing the flood). Nevertheless, most participants declared event 2 to have a higher probability. The reason is that our brain likes coherent stories containing causal chains that sound plausible. This is the case for statement 2, since California is known for its numerous earthquakes.

Dealing with costs

In the context of numbers there is one area that deserves a closer look: costs. Indeed have researchers found a bunch of heuristics that specifically apply to costs and investments. In the following we want to briefly describe one of them: the Sunk Costs Fallacy.

The sunk costs fallacy is what keeps you eating at a restaurant even after you already have had enough. If you think about it, it does not make any sense to eat any more as soon as you feel like you have had enough – you won’t enjoy eating more and you may actually end up with stomach pain instead. Nevertheless, most people keep eating past that sweet spot, because they think “I already paid for it”. The Sunk Costs Fallacy tells us that money we have already spent is gone anyways and we should not let that influence any decisions in the future. Taking this to a bigger scale it might be better for a company to abandon a failing project instead of investing even more, just because “we have already invested that much into this project”.

(If you want to learn more about “dealing with costs”, check out Mental Accounting.)

Dealing with risks

A special topic in the field of heuristics and biases is how we deal with risks. One of the most important tasks our brain subconsciously carries out all the time is analyzing risks. Constantly evaluating the risks around us was extremely important to our ancestors living along with deadly animals in an all around dangerous environment, and we still do it today. The problem is that our world today is vastly different from the life of our ancestors about 20.000 years ago, while our methods for analyzing risks have not evolved at the same pace. In the preceding sections we have already talked about how our brain only takes the information into account which is easily available – What you see is all there is (WYSIATI). This methodology of our mind is also known as the Availability Heuristic and it also applies to our automatic risk analysis. Our ancestors living thousands of years ago faced dozens of potentially deadly risks a day and concentrating on the ones posing a direct threat was a necessity to stay alive. While the risks we face today are vastly different, we still unconsciously apply the same heuristic – leading to an ever growing gap between our risk model and reality. This gets obvious when considering the constant fear of terror and its manifestation in huge budgets allocated to anti-terror measures by many countries. Statistics prove that many incidents are a lot more likely to kill people than a religiously motivated fanatic, including but by far not limited to getting hit by a car or dying of food poisoning. But still the USA spent at least ten times the amount of the budget of the Food and Drugs Administration on the “war against terror”. The effect of overestimating risks simply because we associate vivid images and memories with them is multiplied by the media. Vivid and sometimes exaggerating reports of potential dangers can lead to fear among the audience, in turn leading to even more reports by the media. A vicious circle comes to life, known to researchers as the Availability Cascade. In the worst case, this can lead to total overreaction and panic as demonstrated by the Alar Scandal during the sixties in the USA, an incident where a report that a certain pesticide used on apples potentially could cause cancer (that was later debunked as mostly false) led to tons of fruits getting destroyed.

Risk aversion

Another effect that can be explained by our ancestral roots is our severe aversion of risks, an effect that was intensely studied by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky – eventually contributing to their receipt of the Nobel prize in economics. For quite a long time it was believed that losing 500$ or winning 500$ would both represent changes of the same amount of utility – only in opposite directions. Kahneman and Tversky discovered that this is in fact not true by presenting the following two problems to study participants:

- What do you choose? A sure gain of 900$ or a 90%-chance of gaining 1000$

- What do you choose? A sure loss of 900$ or a 90%-chance of losing 1000$

According to the utility theory participants would either take the chance in both cases or the sure gain and the sure loss, but in reality they behaved differently. While most participants chose the safe option when faced with a possible gain, they mostly decided to take the chance in face of a possible loss. People are more likely to take risks when all their options are bad, because they hope to miss the worst option, even if only at a small chance. When facing a bet with possible positive outcome on the other hand, people very much try to avoid losses if possible. Research has shown that for a bet in the form of “a 50%-chance of winning x$ and a 50%-chance of losing y$”, x needs to be nearly double the amount of y for people to take the bet. Kahneman and Tversky published their findings as the new prospect theory, which was part of the reason why they were later awarded the Nobel Prize of economics.

Biases, biases, biases…

As you can see, there are numerous biases. We wanted to provide you a quick overview to some of the most famous biases. If you want to learn more about the other biases, you can click here to get a list of over 100+ more cognitive biases.

Talking about security

As we’ve seen in the previous section, there are numerous flaws in our decision making process, but how do they influence decisions we make in the context of security? Bruce Schneier is one of the leading researchers in the intersection of psychology and security. He wrote a very interesting paper named “The Psychology of Security” [1], in which he discusses the arising challenges.

Before we want to dive into security decisions, there is one more thing we want to mention. As Schneier states, one very important aspect of security decisions is, that we always have to commit to a trade-off. In every security decision, you trade security against things like time, convenience, liberties, money, capabilities… A few years ago, when an interviewer asked Schneier about 9/11, he mentioned the following example: “Want things like 9/11 never to happen again? Thats easy, simply ground all the aircrafts”.

You can feel safe, even if you are not. The other way around you might not feel safe, although you are. This is an absurd problem we are facing. We need to recognize that “security is both a feeling and a reality. And they’re not the same” [1]. As we learned there is System 1 (“feeling safe”) and System 2 (“the reality”). The problem is the following: “The more [our] perception diverges from reality […], the more your perceived trade-off won’t match the actual trade-off” [1]. This is the reason why it’s so crucial to stop making quick security decisions through System 1. Making quick (and imperfect) decisions, will most of the time lead to a bad trade-off and thus inappropriate behaviour.

According to Schneier, there are five perception biases leading to bad security trade-offs:

- The severity of risk.

- The probability of risk.

- The magnitude of the costs.

- How effective the countermeasure is at mitigating the risk.

- The trade-off itself.

This is also connected to the problem that we overestimate risks that are spectacular, rare, talked about or sudden, in comparison to risks, which are pedestrian, common or just not that much discussed. A popular example would be the fear of terror attacks versus the probability of dying through a heart stroke.

We learned a lot about “Cognitive Biases” in the previous section and are able to connect the dots now. For instance, we overestimate risks that are “talked about” in comparison to risks, which are currently “not discussed”, because of biases like WYSIATI or the Availability Cascade. This is very dangerous in now-a-days media information overflow, because things that are spectacular or rare are also make better stories and therefore getting covered in media. Thus we overestimate the likelihood of e.g. terror attacks in comparison to slow killers like diabetes or heart attacks.

As already mentioned, there is another relevant challenge: sometimes we feel safe, even if we are not – and sometimes it’s the other way around. As Schneier puts it: “We make the best security trade-offs—and by that I mean trade-offs that give us genuine security for a reasonable cost—when our feeling of security matches the reality of security. It’s when the two are out of alignment that we get security wrong.” [1]. So, does this mean we sometimes do irrational decisions that are good anyhow? A topic closely related to this misperception is called the “Security Theater”. This concept describes the fact, that there are a lot of security measures out there, which only make you feel safer, but actually improve the security level just by a small amount. A common example are full-body scanners, which were installed after 9/11. The government invested an insane amount of money into these system, but we all know, that they are mitigating the risk of terrorism only by a small percentage. Nethertheless, they make us feel safer when entering an airport or a plane, and it seems as if this is sometimes more important than the actual security level.

Practical Advice

Talking about flaws in the decision making process of many human beings is one thing, but what really matters is how we can we avoid making bad decision over and over again. Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s answer to that question is pretty straightforward: “We need tricks. We are just animals and we need to re-structure our environment to control our emotions in a smart way” [5]. In other words: How can we avoid using System 1 in relevant situations. We gathered a list of practical tricks to enhance the chance of avoiding statistically bad security decisions. Let’s begin with something pretty obvious.

Take your time to rationalize your decisions as much as possible.

Not rationalizing is the principal cause for most of our bad decisions. We quickly decide by using System 1 and do not take our time to pause and reflect. Nevertheless, rationally rethinking facts and questioning the topic is often a very good start for deciding what to do next. This means using System 2. Doing this is way harder than it seems, because our patterns are so deeply rooted into our minds. Therefore you can use a little trick called “Nudging” – let’s take a quick look at it.

Use “Nudges” to ease the process of making the right decision.

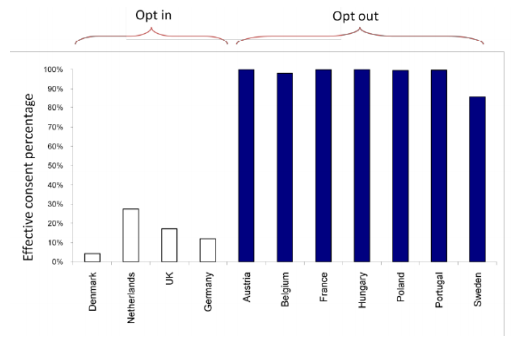

Nudges are a fantastic tool for making better decision. A Nudge pretty much does, what the name says: it influences your decision by giving you a little push into a certain direction. The most famous example might be the use of a picture of a fly in certain urinals. But there are more examples. As a study showed, Nudges are extremely powerful. In a questionnaire, people were asked if they want to be an organ donor. If the question was formulated this way, only a few percent actually agreed to do it. If the question was formulated the other way around (“Do you not want to donate your organs?”), there was a drastic difference in the results (see picture below).

In our opinion, we as software developers should use the concept of nudging to lead our users into making the right decisions. This is our possibility to do something against the flaws in the imperfect human decision making process and we should not abuse it as a tool to take advantage of our users.

Make good security decisions a habit.

This certainly is nothing new. 384 B.C. Aristotle famously wrote: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit”. Nethertheless habits represent the basis of our decisions and therefore influence our actions. Establishing “good security habits” is hard, but it’s definitely worth it. A sample habit would be using 2-factor authentication if possible. And the more often you do it, the easier the trade-off gets for you. To establish these habits, the two previously mentioned advices set the foundation for change. You need to analyze the problem and then create Nudges to ease the process of creating new habits.

Automate security decisions.

This is where the synergy of computers and humans comes into play. Computers do not have a something like a psychology (yet), they are the most genius fools we interact with. There is one thing they can do best and this is thinking rational. This enables us to use them to improve the security trade-offs we make. Let’s think about a small screen besides your front door telling you if all your devices and lights are turned “off”. You would not have to make a trade-off like checking every device by yourself before leaving your home door, which makes the security trade-off a lot easiert. Of course there is a possibility to exploit this system, whichs leads to our daily dilemma of using IT systems…

So, now what?

We are aware of the fact that there is no right or wrong answer to decisions we make and so we cannot provide you the one formula that solves everything. We can never precisely predict the outcome of our decisions, which leads to the problem of choosing between deciding statistically or by intuition. What we can do is taking a step back, pause for a moment, think about our decisions again and give System 2 a little chance to prove, why it was essential for taking human kind to where we are now. If there is one thing we wanted to achieve with this blog post, it’s the following: the next time you enter a supermarket and you see a little sign saying “Max. 12 cans per person”, be the one buying 3 cans instead of 7.

Scientific Questions

While working on our blog post, the following questions came up:

- Should exploiting heuristics and biases be regulated by law and if yes, in which cases? Or in which circumstances is this already the case? In which areas should we pay more attention to this topic?

- When do decision makers (e.g. governments) should decide using a solution, which only makes affected people feel more safe instead of actually making them more safe (Security Theater – Bruce Scheiner, e.g. body scanners at airports)?

- How often does our security awareness diverge from the reality and when (or how often) does it match (Security Trade-off)?

- Because of the current relevancy: How can we counteract the distortion of our perception of reality through media [WYSIATI, Availability Heuristic/Cascade; e.g. overestimation of terror attacks, minority opinions (AfD)]? Should media be bound to always embed news in a context (e.g. compare deaths through terror attacks with food poisoning)?.

- Are there ways to avoid making irrational decisions by using technology (e.g. biotech)? How usefull would such solutions be?

Further Resources

If you are interested in why humans are so immensely error prone or just need some new reading material, you should definitely take a look into the following books:

Thinking fast and slow, Daniel Kahneman, 2011 (probably the most bang for the buck)

Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases, Daniel Kahneman, 1982

Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely, 2008

The upside of irrationality, Dan Ariely, 2012

The Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2001

Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 2007

If you want to read more about security and privacy, Bruce Schneier is the way to go, e.g.:

Data and Goliath, Bruce Schneier, 2015

Interested in human decision making? Here is a talk about a cool new book called “Algorithms to live by”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OwKj-wgXteo

Sources

[1] Bruce Schneier, The Psychology of Security (https://www.schneier.com/essays/archives/2008/01/the_psychology_of_se.html)

[2] Merriam Webster, Psychology (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/psychology)

[3] Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, fast and slow, 2011

[4] List of cognitive biases: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases

[5] Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan, 2007

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.