Note: This article was written for the module Enterprise IT (113601a) during the summer semester of 2025.

Introduction

In various sectors, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming business processes, product development, and competitive landscapes. The availability of open-source AI models, particularly language models, empowers enterprises to accelerate digital transformation, lower barriers to advanced technology, and foster in-house innovation without prohibitive licensing costs. However, as companies increasingly integrate AI into their operations, questions surrounding the true openness, legal compliance, and reliability of these systems become increasingly significant. This article investigates the extension of open-source principles from traditional software to AI, maps the current landscape of enterprise-relevant language models, and critically evaluates the real-world implications of “openness” for organizations navigating regulatory and operational complexities.

Principles of Open Source Software

Open source fundamentally reshapes the way software is developed and distributed, driven by the principle of breaking down barriers to learning, using, sharing, and improving systems. The Open Source Definition (OSD) formalizes these ideas by granting anyone the rights to use, study, modify, and share software, with the goal of fostering autonomy, transparency, seamless reuse, and collaborative advancement [2]. These freedoms, rooted in the Free Software Definition, become the cornerstone of modern software innovation, yielding substantial benefits for both individuals and organizations [2].

Open Source AI Definition (OSAID)

Building on these foundations, the Open Source AI Definition (OSAID) adapts the core concepts of open source to the unique context of AI. While the OSD requires access to software’s preferred form for modification—its source code, unobfuscated and complete [1]—the OSAID extends this requirement to encompass the complexities of machine learning systems [2]. For an AI system to be considered truly open source, not only the full codebase but also detailed data documentation and model parameters (such as weights and configuration files) must be available. This ensures that a knowledgeable user can recreate and meaningfully modify the system, mirroring the practical transparency that open source software enjoys [2].

Another essential feature that both definitions share is the emphasis on unrestricted use and distribution. The OSD mandates free redistribution without licensing fees and prohibits discrimination against any person, group, or field of endeavor [1]. Derivative works must be allowed under the same licensing terms as the original software [1]. Similarly, the OSAID guarantees the right to use, study, modify, and share AI systems for any purpose, with or without changes, and allows licenses to require that modified versions remain equally open [2]. This symmetry guarantees that the proven principles of open source continue to foster innovation and collaboration as they are applied to the rapidly evolving domain of AI.

LLMs versus SLMs

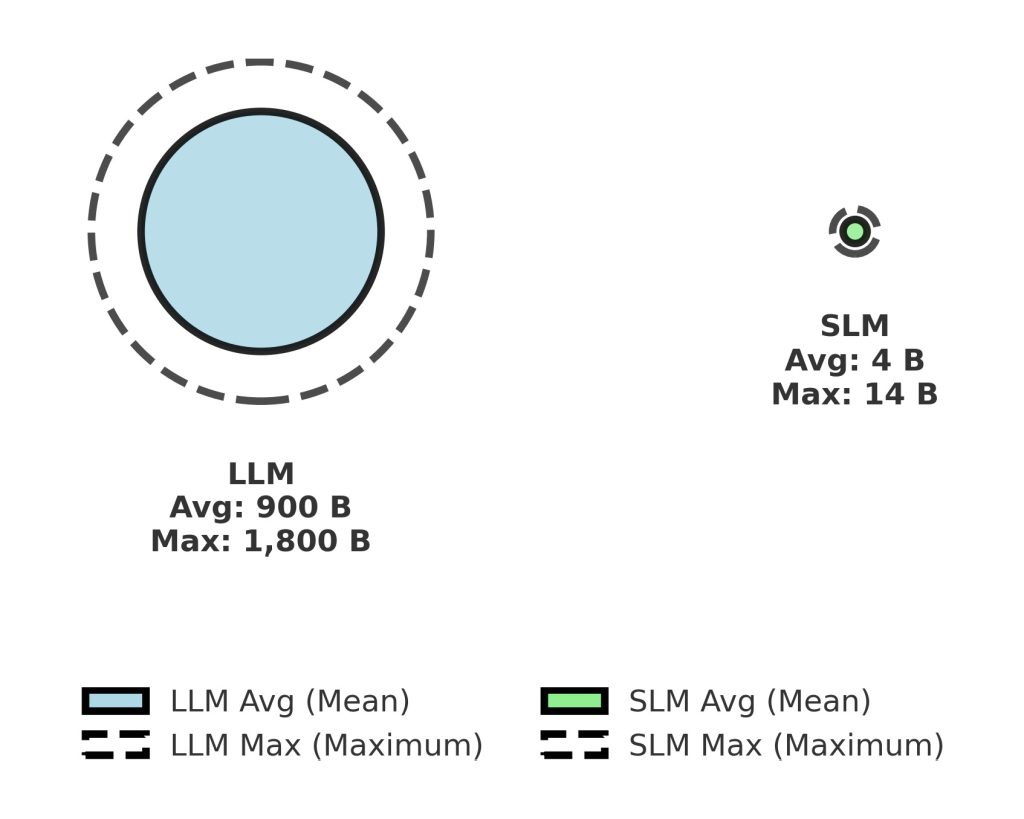

Although AI encompasses a wide range of model categories, this discussion focuses on language models, given their pivotal role in propelling recent advances in generative AI and natural language processing. Large Language Models (LLMs) are a class of “foundation models” that have been trained on massive datasets and are capable of understanding and generating natural language as well as other forms of content for a myriad of tasks [5]. Their performance in text generation, summarization, translation, and conversation plays a central role in popularizing generative AI technologies [5]. Small Language Models (SLMs), while also designed to process, understand, and generate natural language, are distinguished by their more compact architecture: SLMs typically range from a few million to a few billion parameters (see Figure 1), whereas LLMs can contain hundreds of billions or even trillions of parameters (see Figure 1) [3]. This enhancement in efficiency leads to reduced memory and computational demands, rendering SLMs well-suited for environments with limited resources, such as edge devices and mobile applications [3].

Prominent Examples of LLMs

Some of the most widely recognized LLMs include OpenAI’s GPT-3 and GPT-4, which are supported by Microsoft and broadly accessible to the public [5]. Other notable examples include Google’s BERT/RoBERTa and PaLM models [5]. Meta released its Llama models as open source, with Llama 2 positioned as an open foundation model and Llama 3.1 (with 405 billion parameters) also available as open source [5,6]. IBM introduced its Granite model series on watsonx.ai, which serve as the generative AI backbone for other IBM products and are released as open source for commercial use [3,5]. Another prominent open-source LLM is Mistral AI’s Mixtral 8x22B, a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model [5,6].

Prominent Examples of SLMs

In the realm of SLMs, several noteworthy options exist. DistilBERT is a streamlined variant of Google’s influential BERT model [3]. OpenAI offers GPT-4o mini, a more compact and cost-effective version of GPT-4o with multimodal capabilities that accepts both text and image inputs; this model is accessible to ChatGPT users and developers via API, replacing GPT-3.5 [3]. The IBM Granite series also includes SLMs with 2 and 8 billion parameters, available as open source and optimized for low latency [3]. Meta’s Llama series features smaller versions like Llama 3.2, with 1 and 3 billion parameters, including highly efficient quantized variants [3]. Mistral AI’s Ministral models (3 and 8 billion parameters) are additional open-source SLMs [3]. Microsoft’s Phi suite includes SLMs such as Phi-2 (2.7 billion parameters) and Phi-3-mini (3.8 billion parameters), which are available through platforms like Microsoft Azure AI Studio, Hugging Face, and Ollama [3]. Further efficient, compact models include TinyBERT, BabyLLaMA, TinyLLaMA, and MobileLLM, all of which aim to achieve for high efficiency via knowledge transfer and parameter sharing techniques [4].

Accessibility and Open-Source Trends

Access to these models varies: many LLMs are offered via APIs or through platforms like watsonx.ai [5]. However, a growing number of SLMs—and some LLM variants—are released as open source, which accelerates research and development while expanding accessibility to a broader audience [3,5,6]. There is a clear trend toward the development of more efficient models that deliver strong performance even in resource-limited settings [3,4].

Superficial Openness

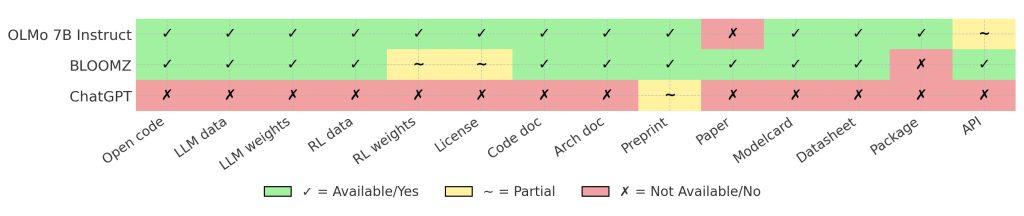

When it comes to AI, “open source” is far from a binary attribute—rather, openness is a composite and graduated property that can vary widely across AI models marketed as open source [7]. A meaningful assessment of how open an AI model truly is must consider 14 dimensions grouped into three main categories: availability (such as source code, language model weights and data, fine-tuning data and weights, and licensing), documentation (including code, model architecture, scientific preprints and peer-reviewed publications, model cards, and datasheets), and access (such as software packages and APIs) [7]. Truly open models like BLOOMZ or OLMo Instruct exemplify high transparency by providing access to training data, source code, and comprehensive scientific documentation (see Figure 2), which together enable thorough scrutiny and independent verification [7].

In contrast, the phenomenon of “open-washing” becomes increasingly common. This occurs when companies present themselves as open while withholding critical details about training and fine-tuning processes—often to avoid scientific, legal, or regulatory scrutiny [7]. A telltale sign of this practice is the so-called “release-by-blogpost” strategy: models are promoted as open, yet their documentation and supporting information fail to meet the standards of scientific publication or peer review (see Figure 2) [7]. Many such models are, at best, “open weight”—they release only model weights under an open license, while key elements like training datasets and methodologies remain undisclosed [7].

Consequences

This superficial approach to openness is not just misleading—it can have serious negative impacts on innovation, research, and the public understanding of AI [8]. Researchers may be unable to properly audit or adapt models, and the broader perception of AI technology can become distorted [8]. Looking ahead, the recently enacted—but only partially applicable—European Union Artificial Intelligence Act (EU AI Act), which exempts open-source models from certain disclosure requirements, may unintentionally incentivize further open-washing if the definition of “open source” is not sufficiently robust and relies too heavily on simple licensing [7]. In reality, genuine, multidimensional openness is essential for risk analysis, verifiability, scientific reproducibility, and legal accountability in AI systems [7].

Open-Source AI Models for Industry and Research

Open-source AI models offer industry—especially in the era of “General Purpose AI” (GPAI) and foundation models—a wide range of advantages that significantly impact the development and deployment of AI systems. By enabling democratized access to advanced technologies, they allow academic researchers, start-ups, and developers to use, modify, and build upon these models without encountering significant financial or licensing constraints [10,11]. This leads to more affordable digital innovation, particularly for the public sector and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that would otherwise struggle with the high costs of proprietary systems [11,13].

A core benefit is the enhanced transparency and interpretability of these models [11]. Since model weights, architectures, and often even training data are publicly available, developers and researchers can better understand the inner workings of these systems, trace and fix errors, and foster reproducibility [11,13]. This openness encourages collaborative innovation and a broader expert community working together to improve and secure the models [11,13]. In sectors such as healthcare, open models can enhance clinical support and public health surveillance by providing access to high-quality AI tools, particularly in resource-constrained environments [11].

Despite these advantages, open-source AI models also bring significant drawbacks and risks. Their openness renders them susceptible to attacks and manipulation, including the introduction of malicious or biased content through adversarial fine-tuning or prompt injection [11]. This can result in hallucinated or inaccurate information, damaging public trust or causing poor decisions in critical domains such as medicine [9,11,12]. The inheritance of bias from training data, especially from web-scraped sources, can exacerbate societal inequalities and lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes [11,12,13].

Operational and Regulatory Concerns

Another concern is the challenge of implementing data protection rights—such as correction, deletion, or access to personal data—since LLMs store information as billions of parameters rather than in traditional databases [12]. This complicates attribution and liability for harms caused by faulty AI-driven decisions, given the complexity and limited interpretability of these models [11,13].

Operational challenges include potentially higher inference times for quantized models [9] and increased computational costs for complex reasoning tasks that require large token throughput [11]. The absence of standardization in documentation and training information for many open-source models further complicates transparency and reproducibility [10]. Lastly, there is often regulatory and legal uncertainty regarding compliance with global data protection and security standards (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA), which can hinder deployment in sensitive industries [11,13].

Conclusion

The integration of open-source principles into AI development offers transformative benefits for industry and enterprise—enabling rapid innovation, reducing costs, and fostering collaboration across organizational boundaries. However, realizing these advantages requires more than nominal openness. Enterprises must navigate the complexities of model transparency, legal compliance, and operational risks, particularly in the face of “open-washing” and evolving regulatory frameworks. As the EU AI Act comes into full effect, the enterprise sector plays a crucial role in demanding and defining what true openness means in practice. Only through genuine commitment to transparency, documentation, and open collaboration can organizations fully leverage the potential of open-source AI, ensuring both competitive advantage and public trust.

References

[1] Open Source Initiative, “The Open Source Definition”, Open Source Initiative. [Online]. Available: https://opensource.org/osd.

[2] Open Source Initiative, “The Open Source AI Definition – 1.0”, Open Source Initiative. [Online]. Available: https://opensource.org/ai/open-source-ai-definition.

[3] R. D. Caballar, “What are Small Language Models?”, IBM Think. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/small-language-models.

[4] Nguyen, C. V., Shen, X., Aponte, R., Xia, Y., Basu, S., Hu, Z., Chen, J., Parmar, M., Kunapuli, S., Barrow, J., Wu, J., Singh, A., Wang, Y., Gu, J., Dernoncourt, F., Ahmed, N. K., Lipka, N., Zhang, R., Chen, X., Yu, T., Kim, S., Deilamsalehy, H., Park, N., Rimer, M., Zhang, Z., Yang, H., Rossi, R. A., and Nguyen, T. H., “A Survey of Small Language Models”, arXiv preprint, 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2410.20011.

[5] [Author(s) not specified], “What Are Large Language Models (LLMs)?”, IBM Think. [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/large-language-models.

[6] Naveed, H., Khan, A. U., Qiu, S., Saqib, M., Anwar, S., Usman, M., Akhtar, N., Barnes, N., and Mian, A., “A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint, submitted July 12, 2023; last revised October 17, 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.06435.

[7] Liesenfeld, A., and Dingemanse, M., “Rethinking open source generative AI: open‑washing and the EU AI Act”, in Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’24), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, pp. 1774–1787, 2024. doi: 10.1145/3630106.3659005.

[8] Greve, E., “Openness Hype and Open Washing: A Critical Analysis of Openness Discourses in Generative AI”, Master’s Major Research Paper, Department of Communication Studies and Media Arts, McMaster University, August 2024. [Online]. Available: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/31548/1/Greve%2C%20Ellie_MRP%20Final.pdf.

[9] Raj, M. J., Kushala, V. M., Warrier, H., and Gupta, Y., “Fine Tuning LLMs for Enterprise: Practical Guidelines and Recommendations”, arXiv preprint, 2024. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2404.10779.

[10] Sangari, E., Abughoush, K., and Azarm, M., “Unveiling the Dynamics of Open-Source AI Models: Development Trends, Industry Applications, and Challenges”, in Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp. 4838–4847, 2025. doi: 10.24251/HICSS.2025.582.

[11] Ye, J., Bronstein, S., Hai, J., and Abu Hashish, M., “DeepSeek in Healthcare: A Survey of Capabilities, Risks, and Clinical Applications of Open‑Source Large Language Models”, arXiv preprint, 2025. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2506.01257.

[12] Lareo, X., “Large language models (LLM)”, TechSonar, European Data Protection Supervisor, in TechSonar Report 2023–2024, p. 6, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.edps.europa.eu/data-protection/technology-monitoring/techsonar/large-language-models-llm_en.

[13] Calanzone, D., Coppari, A., Tedoldi, R., Olivato, G., and Casonato, C., “An open source perspective on AI and alignment with the EU AI Act”, in AISafety/SafeRL Workshop @ IJCAI 2023, Macao, SAR China, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://halixness.github.io/assets/pdf/calanzone_coppari_tedoldi.pdf.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.