Suspicion

It seems a bit odd that with so many well-paid economists, no one has ever considered that a multiplicative system with failure states should be treated differently from an additive system without failure states, until Ole Peters, a physicist, brings the subject up. Something doesn’t seem right about that.

Do economists all conspire to disseminate disinformation and keep the vast majority of wealth in the hands of a select group of “elites”? No, that seems too far-fetched. Nassim Taleb offers a different explanation, he calls “Skin in the game” which is the idea that people don’t properly learn when they have nothing to lose, and economists just regurgitate their ancient theoretical texts without ever being held accountable for applying them and failing.

If this is true, how did Peters, who has even less “Skin” in the economics game than economists discover this giant inconsistency?

At this point, it might be obvious that something doesn’t seem right in this narrative, but ask yourself if you would have been skeptical of the prior claims if the article ended at the conclusion. Would you have left with the idea in your head that Economists are all a bunch of scam artists, thought that this article was nonsensical propaganda, or looked deeper into the topic?

Response

While Taleb and Peters make many correct assertions and the math works out, there is always another side to every story. In this case, Peters has received responses from economists regarding his claims that economics is deeply flawed.

The Paper called “Economists’ views on the ergodicity problem” by Doctor Et al. argues why Peters’ discovery is not as significant as he claims it to be: Peters’ claim that “expected utility theory” secretly” assumes ergodicity is simply wrong since it makes no assumptions about time whatsoever. As a static theory of decisions under uncertainty, it is not intended to be applied to dynamic scenarios, such as the non-ergodic gambles described by Peters.

Moreover, Ergodic Economics is not a new concept, according to economist Ben Golub. It’s a subset of a pre-existing theory of dynamic choice, and mostly boils down to the Kelly criterion[5], which Taleb himself even brings up in his article about ergodicity, but for some reason assumes that economists either are unaware of or ignore.

This means that Peter’s claims are mostly true, “expected utility theory” isn’t suitable for modeling dynamic systems, and the theory he proposes works well for analyzing dynamic systems. He goes off the rails when he claims that economists don’t know any of this already, that he is the first person who discovered any of this old knowledge, and that all of economics is bunk because one theory doesn’t work for all given situations.

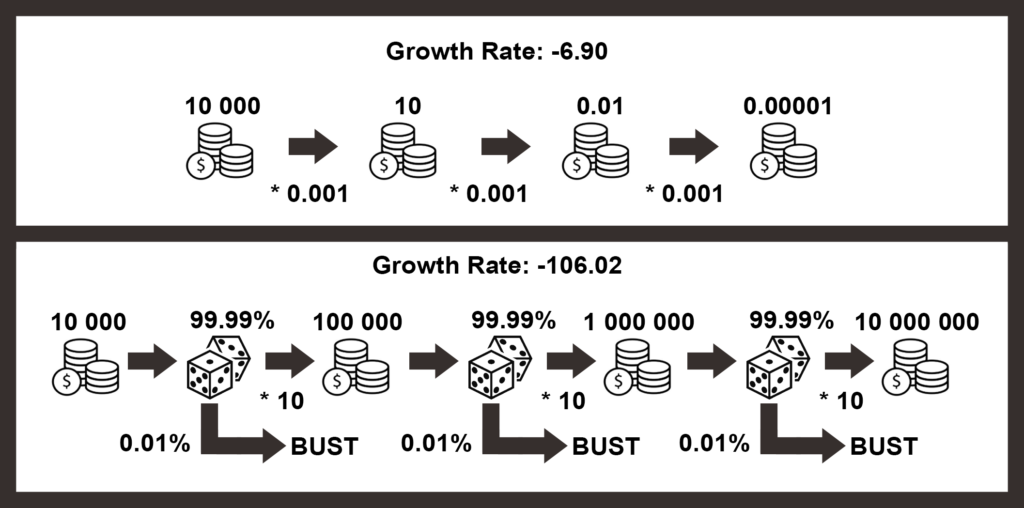

Amusingly the theory Peters proposes as a replacement does not even lead to predictions that reflect the preference of humans in all situations either. Doctor Et al. demonstrate that in a thought experiment of their own, in which we have two processes that are played out in three steps, and both stat with a starting investment of 10 000$.

The first process reduces investment to 0.1% of its current value every step. The second process has a 99.99% chance to multiply the investment by 10 and a 0.01% chance to reduce it to almost nothing every step. Intuitively almost everyone would take the second process, yet Peters Ergodicity Economics formula would predict a lower growth rate of -106.02(9) for the second process compared to -6.90(10) for the first.

(9): 0.9999 * log(10) * 0.0001 * log(10<sup>(−200,000)</sup>) = -106.02

(10): log(0.001) = -6.90

The Revolutionizing of Systems

At this point, it should be clear that the criticisms levied by Peters and Taleb are unfounded, at least in regards to ergodicity. In addition to the rebuttal by Doctor Et al., several other red flags should raise suspicion:

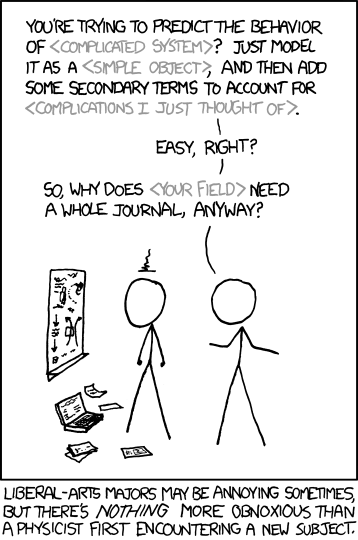

- The Truth Sayer:

- Someone with no training in a field who claims to know more than all the professionals in that field.

- Peters has no training in Economics.

- The Outsider:

- The critique of a field being published without peer review from people in the field.

- Peter’s paper was published in a nature journal despite attacking economics.

- The Revolutionist:

- A problem in the field requiring the complete revolutionizing of the entire field.

- Peters suggested that economics is flawed because it was built on a flawed assumption.

The politically inclined might draw parallels between these red flags and recent political movements or leaders and indeed, these traits are often connected to populism. Now, something isn’t inherently bad just because it is populist. Often the core of populist critiques points out some important truths. But populism trends towards extreme black and white thinking, and that is exactly where the danger lies when we are allowed to explain complicated issues away with simple narratives that confirm our prior beliefs.

Even one of these red flags on its own should raise an eyebrow unless you buy into the conclusion in the first place: That economics is flawed and requires complete revamping. A person who is convinced of a conclusion is likely to believe anyone who presents any plausible argument that supports their beliefs, regardless of contrary information. “Of course economists would make up some reason why their job isn’t bunk, their paycheck depends on it”.

This behavior pattern is known as confirmation bias and is not something that only affects the conspiracy theory inclined. All of us have certain beliefs we hold and would be hard to persuade away from, and we don’t have the time to spend hours researching for every argument we encounter. This, then, is precisely why we have experts and institutions to provide a reliable foundation of knowledge we can draw from to test our beliefs against.

specializing in governance and business climate analysis[6]

Our institutions should not be disregarded so lightly, be it our economic, political, or academic institutions. The standard that needs to be met to justify the complete revamping of those systems should be a high one, and it should be applied equally to all systems. After all, is physics bunk because it does not yet have the answer for all physics-related questions, or should we abolish psychology as a field because of the replication crisis?

As long as we live in a democracy, we depend on our populus being engaged and informed citizens. The constant assertion that our institutions are fundamentally flawed, or corrupt, without sufficient evidence to back up these claims does nothing but erode trust and breed apathy. This leads people to believe that the game is rigged so participating is not worth it in the first place, or to focus all their attention on fixing the wrong problems.

It is important to note that I’m not implying that we should not criticize our institutions or that they are somehow flawless. That would be just the opposite side of black-and-white thinking. Quite the opposite, I believe that there is plenty of valid criticism, and I encourage anyone who seeks to discover these issues. But most things in life are nuanced, and only in rare cases will the destruction and rebuilding of a system lead to more good than damage, so we better be absolutely sure that a revolution is necessary. Most of the time we can incrementally improve systems without having to completely tear them down first.

Citations:

- [1] Ole Peters: The ergodicity problem in economics:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-019-0732-0?proof=t#Equ2 - [2] Nassim Nicholas Taleb: The Logic of Risk Taking:

https://medium.com/incerto/the-logic-of-risk-taking-107bf41029d3 - [3] Jason N. Doctor , Peter P. Wakker and Tong V. Wang : Economists’ views on the ergodicity problem

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-020-01106-x - [4] Randall Munroe: Webcomic – Physicists:

https://xkcd.com/793/ - [5] Ben Golub on Ergodicity Economics:

https://twitter.com/ben_golub/status/1338175642932715520 - [6] Transparency International Corruption Index:

https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index

Additional Reading:

- A blog post with further criticism:

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2020/12/19/in-this-particular-battle-between-physicists-and-economists-im-taking-the-economists-side/ - A bloomberg article covering this topic:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-11/everything-we-ve-learned-about-modern-economic-theory-is-wrong - Peters response to the criticism by Doctors Et al.:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-020-01108-9 - A paper on cognitive biases and populism:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334212085_Wisdom_vs_Populism_and_Polarization_Learning_to_Regulate_Our_Evolved_Intuitions - More on Ergodicity by Peters:

https://ergodicityeconomics.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/ergodicity_economics.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.