Tag: CI/CD

Secure Code, Fast Delivery: The Power of DevSecOps

In today’s fast-paced digital world, security breaches are more than just a risk; they’re almost a guarantee if you don’t stay ahead. Imagine being able to develop software at lightning speed without compromising on security. Sounds like a dream, right? Welcome to the world of DevSecOps! If you’re curious about how you can seamlessly integrate…

Tools for automatic creation of Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)

In times, where software develops at a rapid pace, there is little time to write each component of code yourself. That is why libraries and other tools alike exist – to make our lives easier and to speed up the development process. But how can we keep an overview over all the components we use?…

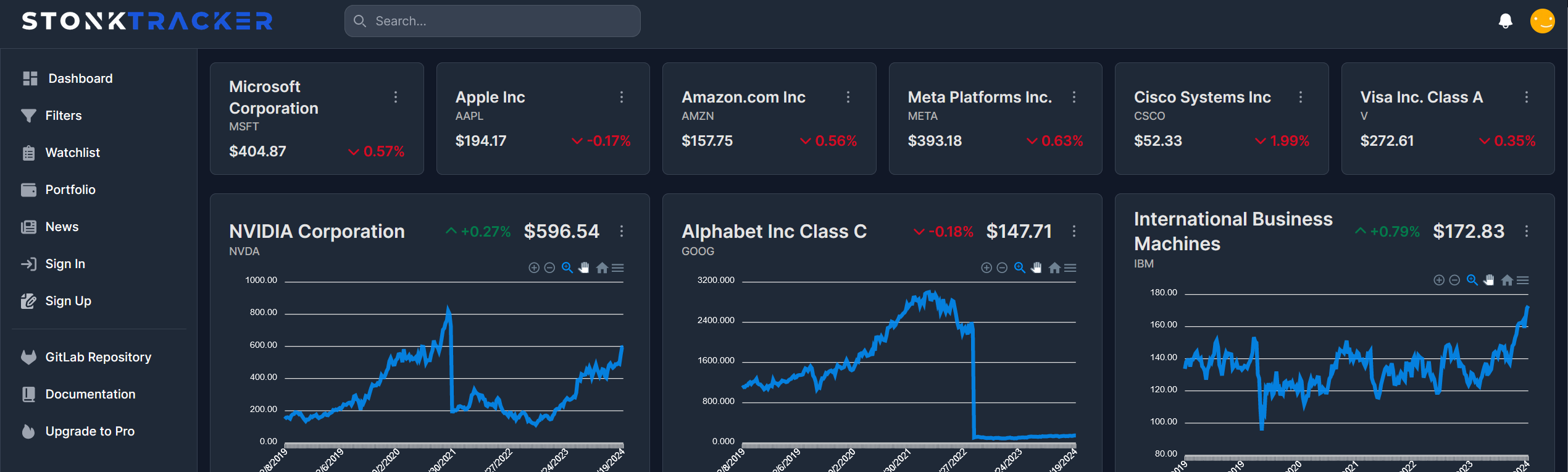

Die Meere der Systemtechnik navigieren: Eine Reise durch die Bereitstellung einer Aktien-Webanwendung in der Cloud

Auf zu neuen Ufern: Einleitung Die Cloud-Computing-Technologie hat die Art und Weise, wie Unternehmen Anwendungen entwickeln, bereitstellen und skalieren, revolutioniert. In diesem Beitrag, der im Rahmen der Vorlesung “143101a System Engineering und Management” entstanden ist, werden wir uns darauf konzentrieren, wie eine bereits bestehende Webanwendung zur Visualisierung und Filterung von Aktienkennzahlen auf der IBM Cloud-Infrastruktur…

CTF-Infrastruktur als Proof-of-Concept in der Microsoft Azure Cloud

Einführung Eine eigene Capture-The-Flag (CTF) Plattform zu betreiben bringt besondere Herausforderungen mit sich. Neben umfangreichem Benutzermanagement, dem Bereitstellen und sicherem Hosten von absichtlich verwundbaren Systemen, sowie einer möglichst einfachen Methode, spielbare Systeme von externen Quellen einzubinden. So möchte man vielleicht der eigenen Community die Möglichkeit bieten, eigene Szenarien zu entwickeln, welche im Anschluss in die…

Splid 2.0 – Die Zukunft des gemeinsamen Ausgabenmanagements

Im Rahmen der Vorlesung “Software Development for Cloud Computing” haben wir uns dafür entschieden, einen Klon der App Splid auf Basis unterschiedlicher Cloud Technologien als Web App zu entwickeln, um uns so die Grundkenntnisse des Cloud Computings anzueignen. Projektidee Bei gemeinsamen Aktivitäten und Gruppenausgaben ist es sehr hilfreich, einfache und effiziente Tools zu haben, um…

FastChat – Your Words, Instantly Delivered

Einführung Herzlich willkommen zu unserem Blogbeitrag über FastChat, einer neuen Web-Chat-Anwendung, die das Kommunizieren im Internet auf ein neues Level hebt. In diesem Beitrag möchten wir euch die Hintergrundgeschichte zu diesem Projekt, unsere Ziele und die Funktionalitäten vorstellen, welche wir erfolgreich umgesetzt haben. Tauchen wir ein! Unsere Idee für FastChat war recht simpel: Wir wollten…

Discord Monitoring System with Amplify and EC2

Abstract Discord was once just a tool for gamers to communicate and socialize with each other, but since the pandemic started, discord gained a lot of popularity and is now used by so many other people, me included, who don’t necessarily have any interest in video gaming. So after exploring the various channels on discord,…

Applikationsinfrastruktur einer modernen Web-Anwendung

ein Artikel von Nicolas Wyderka, Niklas Schildhauer, Lucas Crämer und Jannik Smidt Projektbeschreibung In diesem Blogeintrag wird die Entwicklung der Applikation- und Infrastruktur des Studienprojekts sharetopia beschrieben. Als Teil der Vorlesung System Engineering and Management wurde besonders darauf geachtet, die Anwendung nach heutigen Best Practices zu entwickeln und dabei kosteneffizient zu agieren

- Allgemein, DevOps, Interactive Media, Rich Media Systems, Scalable Systems, System Designs, System Engineering

Designing the framework for a scalable CI/CD supported web application

Documentation of our approaches to the project, our experiences and finally the lessons we learned. The development team approaches the project with little knowledge of cloud services and infrastructure. Furthermore, no one has significant experience with containers and/or containerized applications. However, the team is well experienced in web development and has good knowledge of technologies…

Ynstagram – Cloud Computing mit AWS & Serverless

Im Rahmen der Vorlesung “Software Development for Cloud Computing” haben wir uns hinsichtlich des dortigen Semesterprojektes zum Ziel gesetzt einen einfachen Instagram Klon zu entwerfen um uns die Grundkenntnisse des Cloud Computings anzueignen. Grundkonzeption / Ziele des Projektes Da wir bereits einige Erfahrung mit React aufgrund anderer studentischer Projekte sammeln konnten, wollten wir unseren Fokus…

You must be logged in to post a comment.