Introduction

This semester, our team set itself the goal of developing a game for a Discord bot. Taking inspiration from Hitster and Nobody's Perfect, we created Headliner.

Over three rounds, players receive meta information about a newspaper article, such as what happened, who was involved, where it happened, and when. Based on this information, each player comes up with a suitable headline. In the second phase of the round, all the headlines submitted by the players, as well as the original headline, are displayed, and each player must vote for the headline they think is the original. You gain points for correctly identifying the original headline. You also gain points if other players vote for your headline. After three rounds, the final scores are revealed.

Our main goals were:

- Understanding and using Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

- Queue implementation

- Deployment on AWS

- Scalable deployment (how to decouple things and keep frontend exchangeable)

- AWS S3 bucket storage

- Reproducible setup with Terraform and cloud-config

- Automating the deployment to AWS via gitlab CI/CD pipelines (Platform as a Service)

In this blog post, we share the challenges we faced, the decisions we made, the lessons we learned and the solutions we found.

Tech Stack

We used the following technologies for our project:

- Discord Bot API: To connect our game to Discord and allow players to interact with it.

- Java Spring: For the backend API that handles the game logic and serves the game data.

- Docker: To containerise our application, making it easier to deploy and scale.

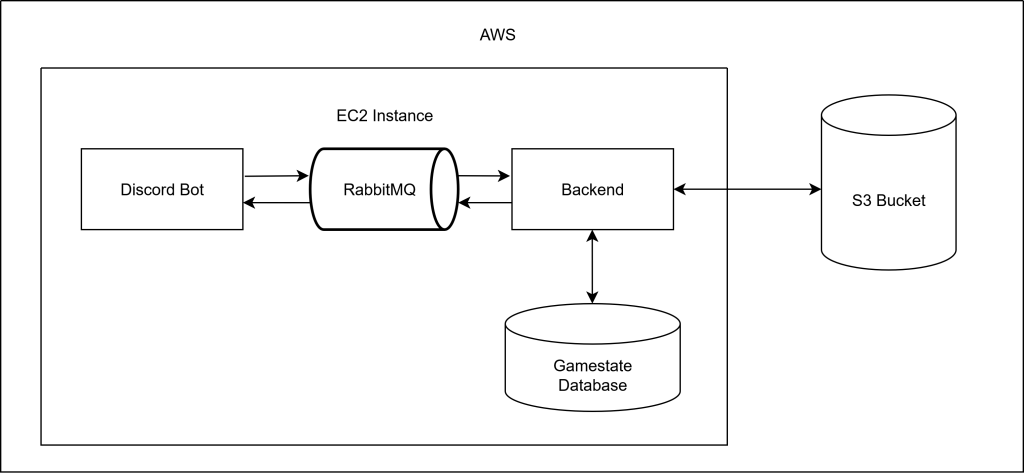

- RabbitMQ: For event-based communication between the frontend (Discord Bot) and backend (Java Spring).

- AWS S3: For storing game data, such as headlines and images.

- AWS EC2: To host our application on AWS.

- Terraform: To automate the deployment of our infrastructure on AWS.

- GitLab CI/CD: For automating the deployment process and ensuring a reproducible setup.

Projekt Structure

The project is structured into three main directories:

- backend: Contains the Java Spring application that handles the game logic and serves the game data.

- discord_bot: Contains the Discord Bot that interacts with users and handles commands related to the game.

- infrastructure: Contains the Terraform configuration files and cloud-config files for deploying the application on AWS.

Architectural Decisions

The architectural decisions in this project were guided by three basic principles that we agreed on at the beginning: Asynchrony, Scalability and Interchangeability. The following chapters dive into each of these principles, exploring how they influenced the architecture and how they are realized in the implementation.

Asynchrony

We decided to use an event-based communication between our frontend and backend. It allows asynchronous and stateless communication.

Both are useful and easier to handle when scaling an application.

Setting up a RabbitMQ was relatively easy. The challenging part was how to distinguish between the different event types that we used in our application. As our frontend and backend are built with different tech stacks, they sort the events based on different attributes by default. We tried out different approaches before we settled on using the type attribute of the message properties for two reasons: Firstly, it makes semantic sense, and secondly, both backend and frontend can easily extract and set the type attribute / the message properties.

Interchangeability

Another requirement we set was to keep the frontend interchangeable, so we could for example plug in a web-view later one.

This brought quite some challenges, but also helped separate the architecture.

Among other things, this was one more reason to use Event-based communication.

It also forced us to strictly define the communication in a way that would allow any frontend to generate the user input events and present the game events.

Scalability

From the beginning, we designed the system with scalability in mind, to fully leverage to potential of AWS and become more familiar with cloud infrastructure in general.

A key enabler of this was the asynchronous, event-based communication. It decouples components and reduces the need for synchronous blocking calls, which become bottlenecks under load. This way, we can scale producers and consumers of events separately based on demand.

Additionally, we deliberately avoided tightly coupling the frontend and backend. This allows us to scale them on different schedules and even deploy multiple frontend instances tailored for different platforms if needed. Our use of RabbitMQ plays a central role here as well, acting as a buffer that smooths out traffic spikes and helps maintain system stability under load.

Automation

Deployment with Terraform

In order to deploy our application to AWS automatically, we set up a Terraform configuration. We opted for Terraform because one of our team members was already familiar with it. Using Terraform, we configured our AWS provider, an internet gateway, a subnet, routing, a security group, and finally our EC2 instance.

Some resources are specific to AWS - like the security group or the correct ami for our desired region - and needed a bit of research and trial-and-error until we figured out the correct configuration.

Additionally, we used a cloud-config file to configure our EC2 instance further.

For security reasons, we have disabled root login and password authentication, meaning that it is now necessary to have one of the stored public keys and the corresponding private key to log into the server with SSH.ssh_pwauth: falsedisable_root: true

Automating Deployment with Gitlab CI/CD

To ensure our deployment process was as smooth and reproducible as possible, we used GitLab CI/CD to automate the build, test, packaging, containerization, and deployment of our entire application stack. This was an essential part of our goal to implement a scalable and reproducible infrastructure using Infrastructure as Code principles.

We split our pipeline into several stages to separate concerns and allow for better visibility and control over each part of the process.

Each component of our application (backend and Discord bot) is built and tested individually, using Maven inside isolated Docker containers. We also included security-related jobs provided by GitLab templates, such as SAST, secret detection, and dependency scanning to catch common vulnerabilities and misconfigurations early in the pipeline.

After building and testing, the application is packaged and containerized using Buildah. Once the images are built, they are pushed directly to our GitLab project's integrated container registry. This made it easy to pull the images later during deployment on the EC2 instance—without relying on any external container registries.

We use the GitLab-managed Terraform state backend. This allowed our team to collaborate safely without worrying about conflicting state files.

After provisioning by the standard terraform stages, a final setup stage SSHs into the newly created EC2 instance, installs Docker and Docker Compose, copies over the environment configuration, and deploys the application using Docker Compose. We also took care to clean up any previous deployments, including stopped containers, images, volumes, and networks, before starting a fresh one.

Here's what the setup stage achieves:

- Automatically installs required dependencies on the EC2 instance.

- Pulls the latest container images from our GitLab container registry.

- Deploys all services (Postgres, RabbitMQ, Backend, Discord Bot) using Docker Compose.

- Verifies the running containers.

This setup made our deployment fully automated from code push to a running instance in the cloud—all while preserving transparency and control through GitLab’s pipeline UI and Terraform state reports.

Encountered Challenges

Throughout the development of this project, we encountered a variety of challenges that tested both our architectural decisions and our technical understanding. From handling the unique scaling limitations of the Discord bot, to designing a reliable timer mechanism without compromising our stateless design and a lot of troubles with AWS.

In this chapter, we take a closer look at the most significant issues we faced and how we approached solving them, sometimes pragmatically, sometimes through a lot of discussion.

Scaling the Discord Bot

One of our main goals in planning this project was to enable us to scale our application easily, which is why we are using containers in the first place.

Typically, when faced with high traffic volumes, some form of load balancer is used to distribute traffic among multiple running instances of the same process.

However, this approach doesn't work for the Discord bot because we are not the ones managing the traffic.

To explain this, we first need to explain how Discord bots communicate with Discord.

Discord uses event-based communication and distinguishes between three types of event: Gateway Events, Webhook Events, and SDK Events.

The only ones relevant to us are Gateway events, which we use to receive updates relating to Discord resources such as channels, guilds and messages.

As their name suggests, these messages are sent via a Websocket-based gateway connection between Discord and our application.

When the bot is started, our application opens and maintains a persistent gateway connection, using a generated API token to identify itself to Discord.

This works perfectly fine as long as only one instance of our application is running.

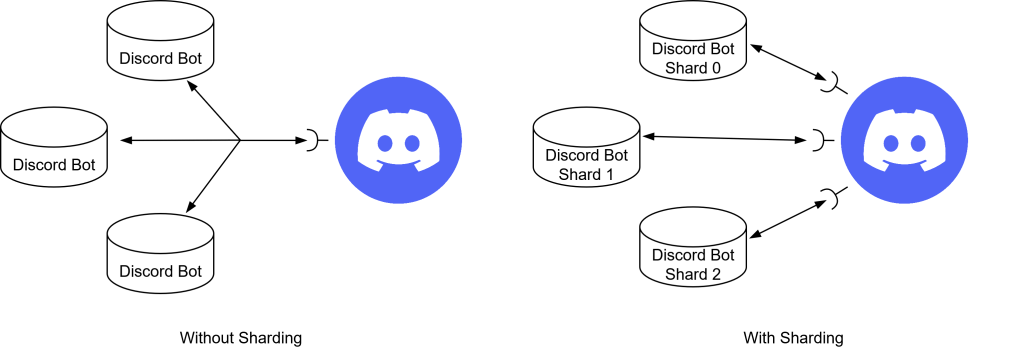

However, starting more than one instance causes problems.

All of our running instances connect to the same WebSocket, so events sent by Discord are received by all instances and processed multiple times.

One way to solve this problem would be by implementing some kind of communication or shared state between the individual instances of the Discord Bot, like, for example, a shared key-value storage.

The instance first receiving the event creates a new entry in the storage containing the event id and its instance id. When another process receives the event, it will see that there already is an entry in the storage and won't further process the event.

Although this approach would be functional, it generates a lot of overhead because each instance still has to receive every event and the shared state requires additional maintenance.

A much better way of dealing with this problem is through a process called "sharding".

When using sharding, each instance will get a shard id, which is essentially just a number that gets increased for each shard, so the first instance is shard 0, the second shard 1 and so on.

Discord opens an individual web socket for each existing shard and all traffic will be split among these web sockets.

To do that, Discord uses the guild id (a unique identifier of a guild) to assign each guild to a shard using this formula:SHARD_ID = (GUILD_ID >> 22) % NUM_SHARDS.

This way events are only received by a single instance while also splitting the total traffic among all instances. Because all events of a single guild are always sent to the same shard, we could even go as far as implementing our discord bot stateful.

Implementing a Game Timer

One seemingly small aspect of the Game Flow sparked a big discussion in our group.

Since each Phase ends after a certain amount of time, some instance in the tech stack would have to track this countdown and initiate appropriate followup steps.

This proved to be especially troublesome, as it would require creating a runtime state in some instance on the stack, which goes against the design principles we have decided on.

To solve this problem, we discussed the different possible approaches.

Frontend

The first possibility would be to have a Timer run on one user's frontend, most likely the one that started the game.

This would be the most straight-forward approach, since that lies outside the main architecture and could therefore have the timer run without violating our ruleset.

But this also has the downside of surrendering the control to the user, which could manipulate it freely, which is arguably not a big problem for a friend-group game.

The main reason against it is the fact that we don't begin with a web-based frontend over which we have control but Discord.

We hesitated from putting it in the Discord Bot for the reason stated before and since that also means a lot of work porting it to a later frontend.

Backend

Once again, putting the timer in the Backend requires one instance to maintain a state for the specific game.

We decided that this is the best location still, since it should have the definitive governance over the game state

Others

The Queue and the Database have also been briefly considered, but discarded due to the Single Responsibility principle.

What we determined to be the best solution in the long run would be a secluded service that regularly scans the database for games that need to advance in the Game State and issue appropriate events.

This could be implemented with AWS Lambdas or similar.

In the end, we settled for a non-optimal solution that would work well enough for now.

In the long run, a better solution would definitely have to be implemented.

Multi-User Developement in AWS

We decided to use AWS for our project because it is a well-known cloud provider and we wanted to learn how to use it.

Although setting up a bucket in AWS S3 was relatively straightforward, we did encounter some difficulties with permissions and access policies.

The first hurdle was setting up accounts and roles in AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM).

One mistake we made was creating an organisation in AWS, which was unnecessary for our project and complicated permission management.

Organisations are useful for larger projects with multiple accounts, but for our project, they introduced unnecessary complexity.

Initially, we created individual accounts for each team member and added them to the organisation to manage permissions.

However, this caused confusion and complications when trying to access the S3 bucket and other resources.

Organisations are usually employed to manage multiple AWS accounts, enabling consolidated billing and centralised management of policies across accounts.

In our case, however, we only needed a single root account for our project.

Having realised this, we created IAM users and roles for each team member within a single AWS account.

This simplified permission and resource management, as we could easily share resources such as S3 buckets and EC2 instances created with the same root account ID.

We also added the AWS IAM default policy (AdministratorAccess) to our IAM users, which gave our team members access to all resources and actions.

This made managing permissions and accessing the S3 bucket and EC2 instances easier.

Permissions in AWS

{"Version": "2012-10-17","Statement": [

{"Effect": "Allow","Action": "*",

"Resource": "*"

}

]}

This policy grants full access to all AWS resources and actions.

While this is suitable for development and testing purposes, access should be restricted in production environments.

Consider implementing a more granular policy that only permits access to the specific resources and actions required for the project.

We created a user with a more limited, programmatic access and an access key, which we use with Terraform to deploy our application.

A lesson learned: "Start with the simplest permissions model and escalate only as needed."

Lightsail vs. EC2

Another challenge we faced was deciding whether to use AWS LightSail for our project.

LightSail is a simplified version of AWS EC2 that is designed to make it easy to deploy applications and containers.

However, we ran into problems with the limits of LightSail's Free Tier, which prevented us from adding volumes to our LightSail instance.

Although we would have preferred to use LightSail because of its simplicity and ease of use, we ultimately decided to use AWS EC2 instead.

The EC2 Free Tier provides greater flexibility and control over instance configuration, enabling us to add extra volumes as required.

If we had had more time, we would have liked to explore LightSail further to see if we could find a solution that did not require additional volumes.

Accessing Random Elements from a Bucket

The headlines used in our game are saved in an object storage, more precisely an AWS S3 bucket.

Each headline is represented by a YAML file containing all relevant information.

Retrieving elements from a bucket is straightforward and can be done by using the path of the object just like your common file system, for example, /images/sample.png.

For our game we need a way to retrieve headlines randomly, which gets hindered by the direct addressation of objects used in S3.

Unlike for example arrays, where one can simply generate a random index to retrieve something at random, S3 buckets are lacking such index.

To solve this problem we need to create an index of our own, by creating an index.yml containing the names of all headline files and the total amount of headlines.

Now, if we need to get a random headline, we need to do the following steps:

- Open the index.yml and get the total amount of headlines

- Generate a random number between 1 and the total amount of headlines

- Select the name at the position of the just generated number

- Use the name to directly address the headline file

One drawback this self generated index has, is that it has to be maintained and the index.yml needs to updated whenever a headline gets added or removed.

But this can be diminished by creating an AWS lambda function that gets triggered by S3 update notifications to update the index file accordingly.

One thing to note here, is that the lambda function should ignore updates to the index file, else it would result in an endless loop, which could get quite expensive.

Final Thoughts

The journey from our initial concept to the final product was long, filled with unexpected twists and turns. However, persevering through these challenges was ultimately rewarding.

Every problem we encountered, every discussion and decision we made, and every change of plan helped us to understand the challenges of developing scalable, cloud-based applications.

This project gave us the opportunity to experiment with many new technologies, such as the Discord Bot API, queue-based communication, AWS server configuration with Terraform, S3 buckets and GitLab CI/CD pipelines for automation.

Initially, we also considered using Kubernetes, as it is widely used in enterprise projects. However, given the amount of configuration required and the fact that our project is too small to properly test and utilise Kubernetes, we decided against it.

Nevertheless, everyone on the team learnt something new during this project, and hopefully you have learnt something too while reading this blog post.

Authors

- Blersch, Lara

- Coglan, Christopher

- Müller, Paul

- Nawrocki, Linus

- Seibold, Frieder

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.